Why interest rates have become a prominent part of the Fed’s focus

- 09.19.25

- Markets & Investing

- Commentary

Review the latest Weekly Headings by CIO Larry Adam.

Key Takeaways

- Chair Powell downplayed the idea of a formal ‘third’ mandate

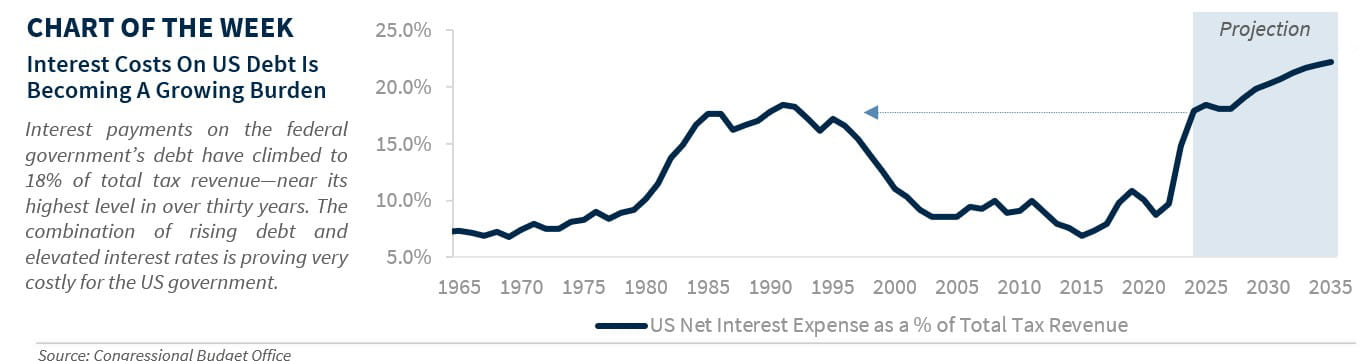

- Soaring debt and elevated interest rates is proving a costly combination

- Keeping long-term interest rates in check is more critical than ever

As summer fades into fall, change is in the air—not just in the weather, but in the economic outlook. Just as the seasons shift, so too does the Federal Reserve’s focus. The Fed operates under a dual mandate: to promote price stability and maximum employment. Lately, employment has taken center stage, prompting the Fed to resume its easing cycle with a 0.25% rate cut this week. In practice, though, the Fed also aims to maintain moderate (some might say low) long-term interest rates—a goal growing in importance as rising debt levels across the economy make borrowing costs more impactful. Balancing inflation, employment, and interest rates is becoming increasingly complex, especially amid persistent fiscal pressures. Below, we explore why interest rates have become a more prominent part of the Fed’s focus.

- Beyond the Fed’s Dual Mandate | While the Fed’s dual mandate—price stability and maximum employment—has long guided monetary policy, a third element is quietly gaining attention. During Stephen Miran’s recent confirmation hearings, he highlighted a lesser-known part of the Fed’s statutory mission: the pursuit of “moderate interest rates.” Chair Powell downplayed the idea of a formal third mandate, suggesting that moderate rates are simply a byproduct of stable prices. Still, in today’s complex macro environment, where mounting debt levels amplify the impact of borrowing costs, we believe the Fed’s focus on interest rates deserves closer attention. Here’s why:

- Rising National Debt—The US national debt is climbing at an unsustainable pace—now over $37t and projected to hit $50t within the next decade. The combination of soaring debt and elevated interest rates is proving costly, with interest payments now the 2nd largest item in the federal budget, consuming 18% of total revenues in FY24—up from 11% in FY19. As pandemic-era debt issued at ultra-low rates gets refinanced at today’s higher levels, the average cost to service the debt has jumped to ~3.4%, up from just 1.5% in 2022. These mounting costs are a key reason why President Trump and the Treasury Dept. have been laser-focused on pushing interest rates lower.

- Housing Affordability Crisis—While the Fed sets short-term interest rates, longer-term rates—like those influencing mortgages—are shaped by market expectations for growth, inflation, and fiscal policy. The sharp rise in long-term yields in recent years has hit the housing market hard, with mortgage rates peaking near 8% in 2023. Amid record home prices, high mortgage rates are especially problematic for affordability. After 125 bps of Fed rate cuts since last September, 30-year mortgages have subsided to 6.4%, the lowest since 2023—a welcome shift for buyers and homeowners that could help revive this depressed part of the economy. Refinancing activity has surged ~60% in recent weeks, and further declines could ease financial pressure and unlock even more consumer spending power.

- Small Business Relief—Small businesses are the backbone of the US economy, driving ~45% of employment and overall activity. But in recent years, they've faced headwinds—optimism, hiring, and investment have all been subdued. While small-cap stocks hit a record high this week for the first time since 2021, they still trail the S&P 500. The culprit? High interest rates. Roughly half of small businesses rely on floating-rate loans, and with average rates above 8%—the highest in nearly 20 years—borrowing has become a major hurdle. That’s why falling interest rates could be a meaningful tailwind for small caps and a much-needed boost for business sentiment.

- The Wealth Effect—Rising asset prices boost household net worth, which in turn stimulates consumer spending. Our economist estimates that every $1 increase in net worth adds ~$0.02 to spending. Since the top 10% of households own 90% of equities and account for half of all spending, upper-income consumers tend to lead the way. Because equity valuations often rise when interest rates fall, keeping rates in check is key to supporting markets—especially now that valuations are in the 97th percentile over the last 20 years. Historically, stocks come under pressure when the 10-year Treasury yield exceeds 4.50%. With a cooling labor market already weighing on lower-income consumers, falling equity prices could hit upper-income households next—dragging down spending across the board.

- Non-Traditional Fed Tools | While the Fed directly controls short-term interest rates through the fed funds rate, it also has tools to influence longer-term rates, albeit to a lesser extent. After the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), the Fed introduced measures like quantitative easing (QE)—large-scale asset purchases designed to lower long-term rates. The Fed can also act as a lender of last resort, buying corporate and mortgage-backed securities during crises, such as the GFC and the 2020 pandemic. These tools, though typically used in times of stress, remain part of the Fed’s broader toolkit. Currently, the Fed is reducing its balance sheet—from a peak of about $9t to ~$6.6t—but could expand it again if needed. Meanwhile, the Treasury is helping manage borrowing costs by issuing more short-term Treasury bills and buying back longer-term debt. Bottom line: with record debt and chronic deficits, keeping long-term rates in check is more critical than ever.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author(s) and the Investment Strategy Committee, and are subject to change. This information should not be construed as a recommendation. The foregoing content is subject to change at any time without notice. Content provided herein is for informational purposes only. There is no guarantee that these statements, opinions or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices and peer groups are not available for direct investment. Any investor who attempts to mimic the performance of an index or peer group would incur fees and expenses that would reduce returns. No investment strategy can guarantee success. Economic and market conditions are subject to change. Investing involves risks including the possible loss of capital.

The information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing material is accurate or complete. Diversification and asset allocation do not ensure a profit or protect against a loss.